Roots & Wings

Although it was rare for playwrights to have much control over casting in the 1590s, Shakespeare’s role as a sharer in the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and his likely involvement in performance suggests a stronger overlap between parts and players. There is, in fact, textual evidence for Kemp’s roles — whose own name replaces the direction for Peter in the second quarto of Romeo and Juliet (1597) and Dogberry in the first quarto of Much Ado About Nothing (1600). Though these facts have been well-documented by Shakespearean critics, fewer scholars have highlighted the potential influence of Will Kemp’s jigs on the parts Shakespeare may have written for him.

Many Shakespearean characters apparently return to life after feigned deaths (Juliet, Hermione, Imogen, Thaisa, Hero, Egeon’s wife Emilia), yet Falstaff’s counterfeit death in 1 Henry IV is particularly interesting because the part was almost certainly written with Kemp in mind – supported by the stage direction “Enter Will” in the quarto.

But more interesting, and rarely explored, is the fact that Falstaff’s ‘death’ parallels the fraudulent death in ‘Rowland’, a popular jig associated with Kemp’s name. The relationship between Kemp’s ‘Rowland’ and his role as Falstaff in both Henry IV plays (1596-7; 1597-8) in fact suggests that Shakespeare’s writing, moulded to and influenced by Kemp’s stage persona, created a form of co-authorship between the two players.

By the 1590s, the jig fell into the hands of the stage clown and became linked to comic songs. Richard Tarlton, followed by William Kemp, catalysed the jig’s increasing popularity around this time. But whereas Tarlton brought jigging to the stage, Kemp’s name has become associated with the jig as a popular and glorious dance form; a way of celebrating the end of a play with the audience through dance.

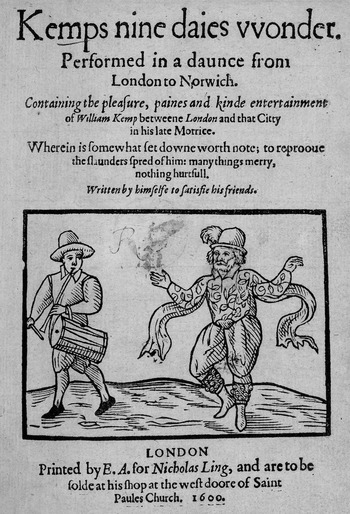

Unlike Shakespeare, Kemp was not a renowned writer: his only published work, Kemp’s Nine Days’ Wonder (1600), describes his infamous morris dance all the way from London to Norwich. He deems himself the “head master of morris dancers” that “hath spent his life in mad jigs and merry jests”. I love this image of Kemp jigging all the way from London to Norwich to settle his debts. Given the journey would take about three days, it is no wonder Kemp thought he had spent a lifetime in a series of mad “jigs” and “jests”.

Shakespeare wrote to Kemp’s requirements because of the latter’s prolific reputation as a public performer and their equal status in the eyes of the company and the public. Of four jigs attributed to Kemp, two have survived: Singing Simpkin (1595); and the German ‘Roland genandt’ (1599). There was probably a whole collection of jigs attributed to Kemp.

We know that Kemp’s and Shakespeare’s partnership ended abruptly in 1599, but we don’t know why. During the five years of Kemp’s association with Shakespeare, he was both performing jigs independently and acting in Shakespeare’s plays. However, the Globe never gained a reputation for jigs – possibly due to the dance form’s typically sexual undertones which the theatre did not want to platform. Perhaps Kemp left the company as Shakespeare became an antagonist to his jigging. Their co-authorship had become problematic for both parties.

Shakespeare’s plays themselves support this argument. The epilogue to 2 Henry IV promises the “author will continue the story, with Sir John in it, and make you merry”, yet Falstaff is conspicuously absent from Henry V. Falstaff’s disappearance is reflected, and perhaps explained, by Kemp’s departure from the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Alternatively, Falstaff’s erasure could have been the reason Kemp left.

The epilogue to 2 Henry IV was potentially written for both public theatre and court performance. In the former context, Kemp would have spoken the epilogue in the build-up to a jig; in the latter, the court epilogue would be spoken by Shakespeare, ending with a prayer for the monarch. The epilogue’s lines which reference dancing are particularly relevant to Kemp’s and Shakespeare’s co-authorship. If spoken by Kemp, the lines “If my tongue cannot entreat you to acquit me, will you command me to use my legs? And yet that were but light payment, to dance out of your debt” suggest a transition to the jig. This is confirmed by the closing lines of the epilogue, “My tongue is weary; when my legs are too, I will bid you good night”. The reference to “light payment” and dancing out of debt could reflect Kemp’s personal debt. Spectators gambled on the failure of his morris dancing venture; publishing Kemp’s Nine Days’ Wonder may have been to encourage payments.

In 1 Henry IV, Falstaff repeatedly references his own death before feigning it. After Prince Hal and Poins trick Falstaff by stealing his horse, he remarks: “Well, I doubt not but to die a fair death for all this”; “I’ll be hanged. It could not be else”. Falstaff’s fear of death and Kemp’s performing become intertwined when Falstaff subsequently tells Hal:

And I have not ballads made on you all and sung to filthy tunes, let a cup of sack be my poison. When a jest is so forward […] I hate it.

The 1987 Oxford Shakespeare edition suggests “ballads” are referenced here because they “castigate deplorable behaviour” and “One could hire a ballad-writer to accuse one’s enemies” (1987). Yet we know from Kemp’s Nine Days’ Wonder that ballad makers were distrusted, as Kemp himself explains: “every day’s journey is pleasantly set down, to satisfy his friends the truth, against all lying Ballad-makers” (1600). Falstaff’s reference to ballad making not only links to Kemp’s own musicality, but reinforces the audience’s mistrust of Falstaff, who is himself a “lying Ballad-maker”.

Falstaff’s final line before his supposed death, “Nay, you shall find no boy’s play here, I can tell you”, is ironic given his playful conceit. After Falstaff “falls down as if he were dead”, the director can choose whether he appears dead or not. If the latter, Falstaff can still communicate with the audience.

This communication while ‘dead’ appears in Kemp’s jigs. David Wiles describes Rowland as keeping “up a running commentary to the audience […] even when acting dead” (1987). In Singing Simpkin, Simpkin achieves this aim while remaining hidden inside a chest. Falstaff’s feigned death seeks praise from Prince Hal; Rowland’s ‘death’ similarly invites newfound praise and affection from his lover Peggie. Rowland’s friend Robert orders him to “Lie down, thyself concealing, and hear what they may say”. Robert then informs Peggie of “tidings drear”: the false news that “Rowland’s life is ended.”

Both Falstaff’s and Rowland’s pretend deaths, however, are not met with the desired effect. Prince Hal brutally states, “I could have spared a better man”, while Peggie is about to leave with the Sexton before Rowland reappears. Both characters remain lying ‘dead’ on stage, expecting their fortunes to change as a result. This makes the ensuing conversations, and accompanying disappointments, all the more amusing.

Falstaff presents rising and counterfeiting through false death as a competition which he must win, creating a similar atmosphere to that in ‘Rowland’ between the eponym and the Sexton. The Sexton tells Peggie, “O sweetest love, forget him” and “Turn now to me and choose me”, to which Rowland responds (presumably as an aside to the audience), “I’ll rob thee of thy breath”.

Although the competition in 1 Henry IV and ‘Rowland’ occurs in different contexts – the former in terms of battle and the latter as a battle between lovers – the presence of false deaths and competition in each establishes a connection between Kemp’s jig and his role as Falstaff. After Falstaff’s ‘death’, Prince Hal exits; then “Falstaff riseth up” and meditates on counterfeiting:

Counterfeit? I lie, I am no counterfeit. To die is to be a counterfeit, for he is but the counterfeit of a man who hath not the life of a man; but to counterfeit dying, when a man thereby liveth, is to be no counterfeit, but the true and perfect image of life indeed.

Despite his counterfeiting, Falstaff persuades the audience that his feigned death (and character) is actually “the true and perfect image of life”. He then contemplates Hotspur’s body in relation to meta-theatricality: “though he be dead. How if he should counterfeit too and rise? […] Why may not he rise as well as I?” . Here, Falstaff reminds the audience that the actor playing Hotspur will too rise at the end of the scene (1996). He then remarks: “By my faith, I am afraid he would prove the better counterfeit”. Similar to ‘Rowland’, this comment intertwines competition with feigned death.

When Bart van Es argues Shakespeare’s co-authorship was “largely or entirely confined to the first and final phases of his development,” the years he was closer to fellow playwrights than actors (2013), he confines co-authorship to its most literal and textual sense. In fact, Shakespeare’s relationship with Kemp became a form of performance-based co-authorship.

Kemp’s jigging after plays, alongside the jig references made by or directed towards Falstaff in 1 Henry IV, denote how Kemp’s dancing talent shaped the parts he played. Moreover, the counterfeit death in Kemp’s ‘Rowland’ links to Falstaff’s feigned death in 1 Henry IV, suggesting Kemp’s prolific reputation as company clown revolved around shared comic performance traits – expressed on stage through both acting and jigging. Shakespeare is not only “a playwright who draws energy from collaboration with other writers” (van Es, 2013), but one who gained inspiration directly from his star performers.

Roots & Wings

Further reading:

Bart van Es, Shakespeare in Company (2013)

Nora Johnson, The Actor as Playwright in Early Modern Drama (2003)

William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1 (1596-7); Henry IV, Part 2 (1597-8); Henry V (1598)

David Wiles, Shakespeare’s Clown: Actor and Text in the Elizabethan Playhouse (1987)